Introduction: The Evolving Chain-of-thought

In this post I focus on peer-reviewed papers from the last year or two. Most of these papers focus on techniques that aim to improve upon the commonly used chain-of-thought (CoT) approach, especially for tasks requiring complex reasoning. It’s not an exhaustive list by any means, but rather my summaries of papers I’ve been reading recently. It’s worth noting that many of these papers use weaker LLMs than today’s top models. As such, I put less emphasis on the results reported (which is often hard to reproduce anyway) and more on the ideas and where they may be applicable. In addition, many benchmarks are not that reflective of real world usage, which is why often doing well on these benchmarks doesn’t mean the model is actually good for a real world task you care about.

One might wonder how relevant is prompt engineering today? While newer models may have internalized many good prompting practices, there’s still a vast ecosystem of models and tasks that benefit greatly from well-crafted prompts. Prompt engineering isn’t dying, but it’s evolving.

Before we dive in, let’s recall a basic example of a CoT demonstration:

Q: Take the last letters of the words in "Willie Valeria Zane" and concatenate

them.

A: Let's think step by step. The last letter of "Willie" is "e". The last letter

of "Valeria" is "a". The last letter of "Zane" is "e". Therefore, the answer is

eae.

This only needs one pass through the language model. This efficiency, combined with its impressive performance on a variety of tasks, has made this simple technique the go-to choice for prompting. For certain tasks, though, straightforward techniques that build on top of CoT prompting can yield even better results.

When One Answer Isn’t Enough

Sometimes we can get a better response from the LLM by exploring multiple reasoning paths. For example, we can generate multiple responses, pick the best one, or let the model improve its first attempt. That’s essentially what Self-Consistency and Self-Refine do.

Self Refine (Neurips 2023)

Paper: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback

Code: https://github.com/madaan/self-refine

Self-Refine centres on the LLM providing its own feedback. It’s an iterative process where, in each round, a response is generated, followed by a feedback pass from the LLM. Here’s the essence:

- Draft the initial solution

- Review and critique the output

- Apply feedback

- Produce an improved solution (based on the original problem, with all previous solutions and their feedback included in the refined-prompt)

- Repeat as necessary

One model does it all. The key is a feedback prompt with instructions and examples to guide the feedback. Essentially, this method automates the iterative prompt refinement typically performed manually by users.

Tests with GPT-4 showed interesting results:

- Most improvements happen in early iterations (this is good)

- Boosted performance across multiple task; Math was the exception, showing minimal gains (GPT-4 tends to trust its math too much)

- Task-specific feedback works best, but watch for overfitting

The downside? Multiple sequntial passes can be too slow and expensive.

Self-Refine Example

One of the tasks in which they observed the highest gains compared to the base models is Constrained Generation, where the model is asked to generate a coherent sentence containing all words/concepts given by the user. The following example is based on few-shot prompting to guide model outputs, but the authors claim that Self-Refine works in zero-shot setups as well.

Task: Create a sentence using these words: card, chip, deal, dealer, table.

Round 1:

AI: "A dealer offers a card to people at a table."

Self-Check: Missing words: "chip", "deal"

Result: ❌ Not all words used

Round 2:

AI: "The dealer dealt each person at the table and offered them a card."

Self-Check: Missing word: "chip"

Result: ❌ Still not perfect

Round 3:

AI: "The dealer dealt each person at the table a chip and offered them a card."

Self-Check: All words used! ✓

Result: ✅ Success!

It’s important to note that the secret sauce is a task-specific feedback prompt. For example:

Words: ['beat', 'drum', 'pen', 'sit', 'use']

Sentence: A man uses a drum to beat a pen.

what words from the word list are missing from the sentence?

Feedback: sit

Words: ['chair', 'clipper', 'cut', 'hair', 'sit']

Sentence: A girl sitting on the couch with her hair up.

what words from the word list are missing from the sentence?

Feedback: clipper, cut, chair

Does Feedback Matter?

Can we just generate multiple outputs instead of refining using feedback? The authors ran an experiment to validate this. They used the LLM to generate 4 samples (without any feedback and refinment) and asked humans to annotate if a single reponse generated by Self-Refine is better than all 4 samples genreated. They reported scores only for two tasks - acronym generation and sentiment reversal. Their results clearly show that humans preferred the Self-Refine generations more often. However, they don’t mention how they generated the multiple samples. It seems they used ChatGPT so I’m assuming they just ran it four times per input, rather then trying a more common sampling approach. Experimental setup matters and it seems they overlooked this one.

This experiment is actually a good segway to the next paper.

Self Consistency (ICLR 2023)

Paper: Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models

Code: N/A

The authors nicely refer to this appraoch as “it acts more like a “self-ensemble” that works on top of a single language model”.

Self-Consistency is a simple idea:

- Start with a good CoT prompt

- Generate multiple responses (5-40 answers)

- Pick the most common response (majority voting to pick the most “consistent” answer)

How to generate multiple responses? They tried different sampling techniques (like temperature sampling). They did an ablation study and concluded that self-consistency is generally robust to sampling strategies and parameters.

Why it works:

- More diverse responses than beam search decoding (they compared the two)

- Robust across different sampling methods

- Popular in research, proven effective

The catch? While they showed gains with 5-10 samples, the best results come from using around 40 samples. That’s a lot of generations, which is not very practical.

For the curious reader, similar approaches include:

- Reflexion (Shinn et al., NeurIPS 2023)

- Self-Correction (Welleck et al., ICLR 2023)

- LEAP (I cover this paper in the Appendix)

Active Prompting: Finding the Perfect Examples (ACL 2024)

Paper: Active Prompting with Chain-of-Thought for Large Language Models

Code: https://github.com/shizhediao/active-prompt

Writing CoT examples isn’t always easy. You want good examples that will improve the model performance, like examples that the LLM doesn’t handle well yet. This paper automates this step, inspired by active learning from more traditional ML. Here’s how it works:

- Run each task through the LLM multiple times

- Find where the LLM gives mixed answers (uncertanity estimation step)

- Use these “confusing” cases as teaching examples

You don’t need labeled answers to find where the LLM struggles. Also, all the heavy lifting happens offline when building the prompt.

Two ways to spot LLM uncertainty:

- Disagreement: Count different answers / total attempts

- Entropy: Also considers answer distribution

To explain the difference: Two unique answers distributed equally in 10 samples would have a higher entropy (higher uncertanity) than two unique answers with 9/10 identical samples. Disagreement would be the same in both cases.

What didn’t work? Asking the LLM how confident it feels. It tends to overestimate itself (a sign of AGI? :)). A better approach was to use the model’s log probaiblities but that is not always available.

Extra read: Automatic chain of thought prompting in large language models (aka. Auto-CoT) also aims to improve examplers’ diversity automatically. It samples questions with diversity and generates reasoning chains to construct CoT examplers. It takes it a step further as it also annotates the exampler unlike in the adaptive prompt work.

Combining Natural Language with Code

For tasks that require numerical computation, the idea is to let the LLM do the reasoning and language understanding, and delegate the actual computation to a generated program. The motivation for this is that LLMs are prone to arithmetic calculation erros, and struggle wtih complex computations, but are good at generating code. There has been a lot of work on code generation from natural lanauge using LLMs, like SQL, Python, etc. Two papers that came out about the same time follow this paradigm to help with various tasks.

Program of Thoughts (TMLR 2023)

Code: https://github.com/TIGER-AI-Lab/Program-of-Thoughts

Works in this area mostly differ is in their intermidate representation, which could be a set of equations, Python code, pseudo code, etc. This work uses Python. It breaks the problem into a multi-step ‘thought’ process and binds semantic meanings to variables to help ground the model in language. Let’s see how it works for a typical math word problem.

Josh decides to try flipping a house. He buys a house for $80,000 and

then puts in $50,000 in repairs. This increased the value of the house

by 150%. How much profit did he make?

Note that GPT-4o (as of Sep 20, 2024) struggles with this question and answers it incorrectly. It fails to generate the correct equations. In a typical chain-of-thought reasining the demonstartion would look something like this:

Let's break it down step by step. Josh bought the house for $80,000.

He spent $50,000 on repairs. This means that his total investment is

$80,000 + $50,000 = $130,000...

As you can see, the LLM does everything, including the calculations. Or as my favorite LLM puts it nicely “Traditional chain-of-thought treats your AI like a student showing their work. Program of Thoughts treats it like a programmer writing code”. Let’s look at how it handles this house-flipping problem:

Question: Josh decides to try flipping a house. He buys a house for $80,000

and then puts in $50,000 in repairs. This increased the value of the house

by 150%. How much profit did he make?

# Python code, return ans

cost_of_original_house = 80000

increase_rate = 150 / 100

value_of_house = (1 + increase_rate) * cost_of_original_house

cost_of_repair = 50000

ans = value_of_house - cost_of_repair - cost_of_original_house

The authors used the SymPy library to execute the code. The model picks up this code structure from demonstration examples in the prompt. You can design more complex demonstartions where the program is an intermidate step.

Program-aided Language Models (Poster, ICML 2023)

Paper: PAL: Program-aided Language Models

Code: https://reasonwithpal.com

Similar to Program of Thoughts, but uses more complex Python, like leveraging data structures instead of just arithmetic. They also focus on CoT-style reasoning chains. One nice experiment they performed was including the answers in the prompt to assess whether the LLM could replace the interpreter. They observed a significant decline in performance, proving that code execution, not just prompt formatting, drives the improvements. They also found that meaningful variable names are important, leading to better performance than using random names, as you might expect.

Demonstartion example:

# Q: I have a chair, two potatoes, a cauliflower, a lettuce head, two tables, a

cabbage, two onions, and three fridges. How many vegetables do I have?

# note: I'm not counting the chair, tables, or fridges

vegetables_to_count = {

'potato': 2,

'cauliflower': 1,

'lettuce head': 1,

'cabbage': 1,

'onion': 2

}

print(sum(vegetables_to_count.values()))

Related work: Binding Language Models in Symbolic Languages from ICLR 2023.

Multi-step Chain-of-Thoughts

Humans often tackle a complex problem by breaking it down into smaller, manageable pieces. This is the same idea just with LLMs.

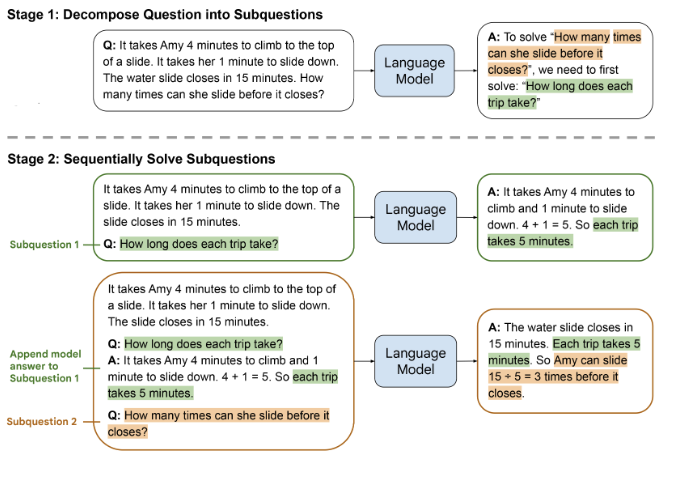

Least-to-Most Prompting (ICLR 2023)

Paper: Least-to-Most Prompting Enables Complex Reasoning in Large Language Models

Code: N/A

The authors claim that CoT perform poorly on tasks that require solving problems harder than the exemplars shown in the prompts (easy-to-hard generalization). They propose a two step approach:

- Decompose the task into subproblems (using a prompt with few-shot examples showing how to decompose)

- Solve each subproblem sequentially (using a seperate prompt), carrying forward previous answer

The main limitation is obvious. You need to make multiple LLM calls sequntially. The other limitation is that you need some trail and error to get the prompts working well for your problem and domain.

The following image from the paper explains this approach best.

While this approach makes a lot of sense, it’s worth noting that their results show that there are two important considerations to make:

- How trivial is to decompose the task?

- How many steps are needed to solve the problem?

They show for example that on the GSM8K dataset (Grade School Math), least-to-prompt significantly improves on CoT only on questions that require at least 5 reasoning steps. It kinda makes sense. Think of the problem of last-letter concatenation. If the inputs has 2-3 words, one pass with CoT is likely to suffice. But for 10 words, the LLM is likely to get lost somehwere in the middle. Decomposing the problem to 10 sub-problems is expensive but likely lead to the right solution. (they actually reported 100% accuracy on this task)

To summarize the key implementation notes:

- Requires careful prompt engineering for your specific domain

- Only worth the extra LLM calls for truly complex problems (5+ steps)

- Sequential processing means higher latency

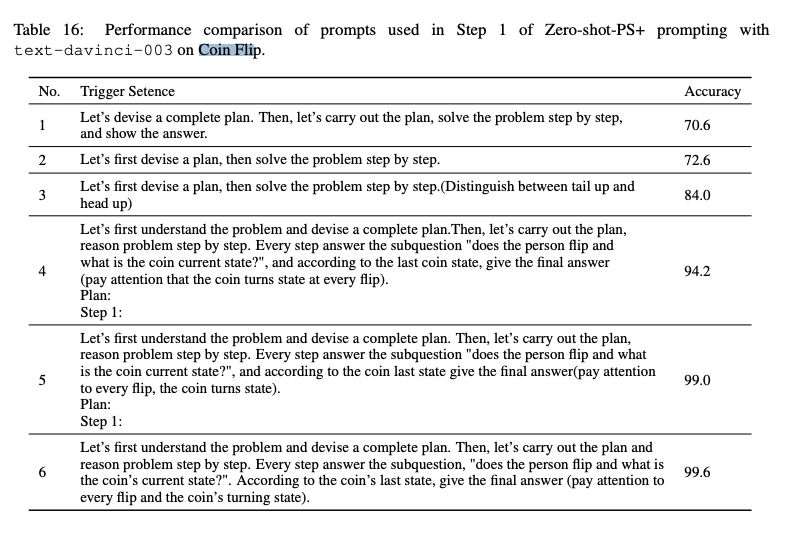

Plan-and-Solve Prompting (ACL 2023)

Paper: Plan-and-Solve Prompting: Improving Zero-Shot Chain-of-Thought Reasoning by Large Language Models

Code: https://github.com/agi-edgerunners/plan-and-solve-prompting

This work is prompt engineering at its finest; tweaking instructions until they work better. Plan-and-Solve prompting boosts zero-shot reasoning accuracy by 20%+ with one simple change: Replace “Let’s think step by step” with a two-phase prompt that plans first, solves second: “Let’s first understand the problem and devise a plan to solve the problem. Then, let’s carry out the plan and solve the problem step by step”. Unlike Least-to-Most prompting, this happens in a single LLM call. They also showed that many calculation errors the LLM makes can be addressed by more detailed instructions.

Coin Flip Example

Coin Flip is a toy symbolic reasoning task introduced in the original CoT paper. This task asks the model to answer whether a coin is still heads up after people either flip or don’t flip the coin (e.g., “A coin is heads up. Phoebe flips the coin. Osvaldo does not flip the coin. Is the coin still heads up?” → “no”). The following table from the paper shows how adjustments to the prompt can have a significant impact on the results.(text-davinci-003 is an older openai model from the GPT-3 family, not competitive today)

Prompting Frameworks

A framework that implements common prompting techniques and simplifies experimentation with different ones would be really helpful. If you’re aware of any good options, do let me know! (it’s worth a seperate blog post). I’ve tested these briefly but haven’t found my perfect fit yet.

- DSPy Full-featured but looks overkill for what I need

- ELL: Treats prompts as programs. Clean concept, lighter implementation.

- PromptHub: Ready-to-use prompt library with support for chaining prompts together

Appendix

One more Self-Refine style paper

Paper: In-Context Principle Learning from Mistakes (ICML Workshop on In-Context Learning, Poster)

Code: N/A

Similar to self-refine, this work uses the LLM to reflect on its own previously generated outputs. But instead of having LLMs check their work repeatedly, they learn good principles from their mistakes upfront (no need to generate multiple samples at test time). Their experiments showed only modest gains, yet I found the approach interesting nonetheless.

The high-level LEAP (Learning Principles) approach goes like this:

- Run the LLM in zero-shot CoT fashion multiple times on some questions you have gold answers for

- Ask the LLM to evaluate answers against the gold

- For each mistake, ask the LLM to generate low-level principles

- Generate high-level principles from the low-level principles

- Create an enhanced prompt with the low-level and/or high-level principles, with optional few-shot examples (recommended)

First, the low-level prompt:

Question: {question}

Generated Reasoning: {response}

Generated Answer: {generated_answer}

Correct Reasoning: {correct_reasoning}

Correct Answer: {correct_answer}

Instruction: Conduct a thorough analysis of the generated answer in comparison to the

correct answer. Also observe how the generated reasoning differs from the correct

reasoning. Identify any discrepancies, misunderstandings, or errors. Provide clear

insights, principles, or guidelines that can be derived from this analysis to improve

future responses. We are not focused on this one data point, but rather on the general

principle.

Reasoning: <discuss why the generated answer is wrong>

Insights: <what principle should be looked at carefully to improve the performance in

the future>

A low-level learned principle example:

1. The system should be designed to understand the context of the question better.

In this case, it should have recognized that the question was asking for the

duration of existence of the European Coal and Steel Community before it

transitioned into the European Economic Community. Understanding the specific

context and requirements of a question is crucial for generating accurate answers

Then, optionally, the high-level princpiles prompt:

Low-level principles: {low_level_principles}

Create a list of *unique* and insightful principles to improve future responses based

on the analysis above.

Focus on capturing the essence of the feedback while eliminating redundancies.

Ensure that each point is clear, concise, and directly derived from the introspection

results.

Create a numbered list of principles. Leave specific details in place.

Limit to at most 8 principles.

List of Principles:

Learned high-level princples examples:

1. Ensure clarity and precision: Responses should be clear and concise, avoiding any

ambiguity or unnecessary complexity.

2. Maintain relevance: Responses should directly address the query or topic at hand,

avoiding any unrelated

or tangential information.

1. Prioritize uniqueness: Strive to provide unique insights or perspectives in responses,

avoiding repetition or common knowledge.

Final prompt:

Instruction: {instruction}

In doing so, please carefully note the following principles:

Principles: {principles}

---

{few_shot_questions_and_answers}

Q: {test_question}

How well does it work?

- Small improvements with mid-sized models (even when GPT-4 was used to generate the principles)

- Negligible gains with GPT-4/Claude-level models

- No clear winner between high-level vs. low-level principles